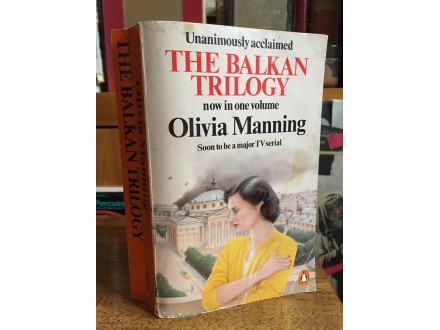

Olivia Manning THE BALKAN TRILOGY

| Cena: |

| Želi ovaj predmet: | 15 |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | BEX Pošta DExpress Post Express Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja) Ostalo (pre slanja) Pouzećem Lično |

| Grad: |

Novi Sad, Novi Sad |

Godina izdanja: Ostalo

ISBN: Ostalo

Jezik: Engleski

Autor: Strani

Dobro očuvano kao na slikama

Retko u ponudi

Olivija Mening

Balkanska trilogija

Olivia Mary Manning CBE (2 March 1908 – 23 July 1980) was a British novelist, poet, writer, and reviewer. Her fiction and non-fiction, frequently detailing journeys and personal odysseys, were principally set in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the Middle East. She often wrote from her personal experience, though her books also demonstrate strengths in imaginative writing. Her books are widely admired for her artistic eye and vivid descriptions of place.

Olivia Manning

CBE

A young woman looks into the camera with a serious expression, her short, wavy hair topped by a hat with veiling.

Born

Olivia Mary Manning

2 March 1908

Portsmouth, Hampshire, England

Died

23 July 1980 (aged 72)

Ryde, Isle of Wight, England

Resting place

Billingham Manor, Chillerton, Isle of Wight, England

Occupation

Novelist and poet

Subjects

War, colonialism, imperialism, displacement, alienation, feminism

Notable works

Fortunes of War

Years active

1929–1980

Spouse

R. D. Smith (m. 1939)

Manning`s youth was divided between Portsmouth and Ireland, giving her what she described as `the usual Anglo-Irish sense of belonging nowhere`. She attended art school and moved to London, where her first serious novel, The Wind Changes, was published in 1937. In August 1939 she married R. D. Smith (`Reggie`), a British Council lecturer posted in Bucharest, Romania, and subsequently lived in Greece, Egypt, and British Mandatory Palestine as the Nazis overran Eastern Europe. Her experiences formed the basis for her best-known work, the six novels making up The Balkan Trilogy and The Levant Trilogy, known collectively as Fortunes of War. Critics judged her overall output to be of uneven quality, but this series, published between 1960 and 1980, was described by Anthony Burgess as `the finest fictional record of the war produced by a British writer`.[1]

Manning returned to London after the war and lived there until her death in 1980; she wrote poetry, short stories, novels, non-fiction, reviews, and drama for the British Broadcasting Corporation. Both Manning and her husband had affairs, but they never contemplated divorce. Her relationships with writers such as Stevie Smith and Iris Murdoch were difficult, as an insecure Manning was envious of their greater success. Her constant grumbling about all manner of subjects is reflected in her nickname, `Olivia Moaning`, but Smith never wavered in his role as his wife`s principal supporter and encourager, confident that her talent would ultimately be recognised. As she had feared, real fame only came after her death in 1980, when an adaptation of Fortunes of War was televised in 1987.

Manning`s books have received limited critical attention; as during her life, opinions are divided, particularly about her characterisation and portrayal of other cultures. Her works tend to minimise issues of gender and are not easily classified as feminist literature. Nevertheless, recent scholarship has highlighted Manning`s importance as a woman writer of war fiction and of the British Empire in decline. Her works are critical of war and racism, and colonialism and imperialism; they examine themes of displacement and physical and emotional alienation.

Early years

Early career

Odnos tradicije i modernizacije u oblastima priključenim Srbiji posle Berlinskog kongresa: Leskovac (1878-1941)

Marriage and Romania

Greece and Egypt

Palestine

Post-war England

The Balkan Trilogy and other works Edit

Between 1956 and 1964 Manning`s main project was The Balkan Trilogy, a sequence of three novels based on her experiences during the Second World War; as usual she was supported and encouraged by Smith.[134] The books describe the marriage of Harriet and Guy Pringle as they live and work in Romania and Greece, ending with their escape to Alexandria in 1941 just ahead of the Germans. Guy, a man at once admirable and unsatisfactory, and Harriet, a woman alternately proud and impatient, move from early passion to acceptance of difference. Manning described the books as long chapters of an autobiography, and early versions were written in the first person, though there was significant fictionalisation. While Manning had been 31 and Smith 25 at the outset of war, Manning`s alter ego Harriet Pringle was a mere 21, and her husband a year older. Manning was a writer by profession, while her creation was not.[135]

Large public building fronted by sentry boxes and a near-empty square.

King`s Palace, Bucharest, Romania, 1941

The first book in the trilogy, The Great Fortune, received mixed reviews, but subsequent volumes, The Spoilt City and Friends and Heroes were generally well-received; Anthony Burgess announced that Manning was `among the most accomplished of our women novelists` and comparisons were made to Lawrence Durrell, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Powell. There were a few unfavorable criticisms, and as usual, they ignited Manning`s ire.[136]

Following the publication of the final volume of The Balkan Trilogy in 1965, Manning worked on her cat memoir and a collection of short stories, A Romantic Hero and Other Stories, both of which were published in 1967.[137] Another novel, The Play Room (published as The Camperlea Girls in the US), appeared in 1969. The book of short stories and The Play Room both contained homosexual themes, a topic which interested Manning. The latter was a less than successful exploration of the lives and interests of adolescents, though the reviews were generally encouraging.[138] A film version was proposed, and Ken Annakin asked her to write the script. The movie, with more explicit lesbian scenes than the book, was all but made before the money ran out; a second version, with a very different script, was also developed but came to nothing. `Everything fizzled out`, she said. `I wasted a lot of time and that is something which you cannot afford to do when you are sixty`; in keeping with her obfuscations about her age, she was actually sixty-two.[139]

The Levant Trilogy Edit

The 1970s brought a number of changes to the household: the couple moved to a smaller apartment following Smith`s early retirement from the BBC and 1972 appointment as a lecturer at the New University of Ulster in Coleraine. The couple subsequently lived apart for long periods, as Manning rejected the idea of moving to Ireland.[140]

Manning was always a close observer of life, and gifted with a photographic memory.[32] She told her friend Kay Dick that, `I write out of experience, I have no fantasy. I don`t think anything I`ve experienced has ever been wasted.[80] Her 1974 novel The Rain Forest showed off her creative skills in her portrayal of a fictional island in the Indian Ocean and its inhabitants. Set in 1953, the novel`s central characters are a British couple; the book examines their personal experiences and tragedies against the background of a violent end to colonial British rule.[141] The book is one of Manning`s lesser-known books, and she was disappointed that it was not shortlisted for the Booker prize.[142]

Early in 1975 Manning began The Danger Tree, which for a time she described as `The Fourth Part of the Balkan Trilogy`;[143] in the event, it became the first novel in The Levant Trilogy, continuing the story of the Pringles in the Middle East. The first book proved `a long struggle` to write, in part because of Manning`s lack of confidence in her powers of invention: the book juxtaposes the Desert War experiences of a young officer, Simon Boulderstone, with the securer lives of the Pringles and their circle.[144] Manning, fascinated by sibling relationships, and remembering the death of her own brother, also examined the relationship between Simon and his elder brother, Hugo. She felt inadequate in her ability to write about soldiers and military scenes; initial reviewers agreed, finding her writing unconvincing and improbable, though subsequent reviewers have been considerably kinder.[145]

period photo of helmeted soldiers with rifles running through dust and smoke

British soldiers at El Alamein during the Desert War

While some parts of the book were inventions, she also made use of real-life incidents. The opening chapter of The Danger Tree describes the accidental death of the young son of Sir Desmond and Lady Hooper. The incident was based on fact: Sir Walter and Lady Amy Smart`s eight-year-old boy was killed when he picked up a stick bomb during a desert picnic in January 1943. Just as described in the novel, his grief-stricken parents had tried to feed the dead boy through a hole in his cheek.[73][76] Manning had long been resentful at the Smarts` failure to include her and Smith in their artistic circle in Cairo. The scene was considered in poor taste even by Manning`s friends, who were also outraged that the quiet and faithful Lady Smart was associated with Manning`s very different Lady Hooper.[76][77] Though both Sir Walter and his wife had died by the time of publication, Manning`s publisher received a solicitor`s letter written on behalf of the Smart family, objecting to the scene and requiring that there should be no further reference to the incident or to the couple in future volumes. Manning ignored both requests.[76] She based the character of Aidan Pratt on the actor, writer, and poet Stephen Haggard,[146] whom she had known in Jerusalem. Like Pratt, Haggard committed suicide on a train from Cairo to Palestine, but in Haggard`s case it followed the end of a relationship with a beautiful Egyptian woman, rather than unrequited homosexual love.[147] After years of complaints about her publisher Heinemann, Manning moved to Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and remained with them until the end of her life.[148] The Danger Tree was a considerable critical success, and though Manning was disappointed yet again that her novel was not shortlisted for the Booker prize, The Yorkshire Post selected it as their Best Novel of 1977.[149] This award followed her appointment as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1976 Birthday Honours.[3][150]

With Field Marshal Montgomery`s Memoirs as her guide, Manning found battle scenes easier to write in the second volume of the trilogy, The Battle Lost and Won. After a slow start, Manning wrote with certainty and speed; the book was completed in a record seven months and published in 1978. The book follows the Pringles as Rommel and the Afrika Korps approach Alexandria, where Guy is teaching. Egypt remains a place of privilege and sexual exchange for the non-combatants and the Pringles` marriage slowly disintegrates.[151]

Final years Edit

Manning was deeply affected by the sudden death in 1977 of Jerry Slattery, her lover and confidant for more than a quarter of a century.[152] Manning`s last years were also made difficult by physical deterioration; arthritis increasingly affected her,[153] leading to hip replacements in 1976 and in 1979 and she suffered poor health related to amoebic dysentery caught in the Middle East.[154] Manning began work on the final novel in The Levant Trilogy, The Sum of Things, in which Harriet agrees to sail home to the UK, but having said goodbye to Guy, changes her mind. The novel describes Harriet`s travels in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, observes Guy`s supposed widowerhood in Cairo after he hears of the sinking of Harriet`s ship, and follows Simon Boulderstone`s injury during the battle of El Alamein and recovery.[155]

The Sum of Things was published posthumously, for on 4 July 1980 Manning suffered a severe stroke while visiting friends in the Isle of Wight. She died in hospital in Ryde on 23 July; somewhat typically, Smith, having been recalled from Ireland, was not present when she died.[3][156] He could not bear to see her `fade away` and had gone to London to keep himself busy. Manning had long predicted that the frequently tardy Smith would be late for her funeral, and he almost was. His mourning period, characterised by abrupt transitions from weeping to almost hysterical mirth, was precisely how Manning had imagined Guy Pringle`s reaction to Harriet`s supposed death in The Sum of Things. Manning was cremated and her ashes buried at Billingham Manor on the Isle of Wight.[3][157]

Manning had long complained about the lack of recognition she had received as a writer and was not consoled when her husband and friends responded that her talent would be recognised, and her works read for years to come. `I want to be really famous now, Now`, she retorted.[9][158] As it happened, her renown and readership developed substantially after her death; a television serialisation of Fortunes of War starring Emma Thompson and Kenneth Branagh finally came to fruition in 1987, bringing her work to a wider audience.[9][159]

Work Edit

Reception Edit

The posthumous popularity of Fortunes of War notwithstanding, most of Manning`s books are rarely read and have received little critical attention.[129][160] Of her books, only Fortunes of War, School for Love, The Doves of Venus, The Rain Forest and A Romantic Hero remain in print.[161] Some of her novels, most often Fortunes of War, have been translated into French, German, Finnish, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Greek, Romanian and Hebrew.[41][162] As in her lifetime, opinions are divided; some assert that her books are `flawed by self-indulgence and a lack of self-judgment`,[163] and criticise portrayals of ethnic and religious groups as stereotyped and caricatured.[164][165][166] Others praise tight, perceptive and convincing narratives and excellent characterisation.[106][167][168] Her plots are often described as journeys, odysseys and quests in both literal and metaphorical senses.[165][169][170] Manning`s talent for `exquisite evocations of place`,[171] including physical, cultural and historical aspects have been widely admired,[41][165] and the critic Walter Allen complimented her `painter`s eye for the visible world`.[166]

Fortunes of War Edit

Manning`s best known works, the six books comprising Fortunes of War, have been described as `the most underrated novels of the twentieth century`[172] and the author as `among the greatest practitioners of 20th-century roman-fleuve`.[173] Written during the Cold War more than sixteen years after the period described, The Balkan Trilogy, set in Romania and Greece, is considered one of the most important literary treatments of the region in wartime, while criticised for the Cold War era images of Balkanism,[45][173] and for Manning`s inability to `conceal her antipathy towards all things Romanian`.[46] The Levant Trilogy, set in the Middle East, is praised for its detailed description of Simon Boulderstone`s desert war experience and the juxtaposition of the Pringles and their marriage with important world events.[3][174] Excerpts from the novels have been reprinted in collections of women`s war writing.[175][176] Theodore Steinberg argues for the Fortunes of War to be seen as an epic novel, noting its broad scope and the large cast of interesting characters set at a pivotal point of history. As with other epic novels, the books examine intertwined personal and national themes. There are frequent references to the Fall of Troy, including Guy Pringle`s production of Shakespeare`s Troilus and Cressida in which British expatriates play themselves while Romania and Europe mirror the doomed Troy.[172][177][178] In Steinberg`s perspective, the books also challenge the typically male genre conventions of the epic novel by viewing the war principally through the eyes of a female character `who frequently contrasts her perceptions with those of the men who surround her`.[177] In contrast, Adam Piette views the novel sequence as a failed epic, the product of a Cold War desire to repress change as illustrated by `Harriet`s self-pityingly dogged focus on their marriage` without dealing with the radicalism of the war, and fate of its victims as represented by Guy and his political engagement.[179]

Other works Edit

Manning`s other works have largely been described as precursors to the two trilogies.[165][166] Her pre-war novel, The Wind Changes (1937), set in Ireland, anticipates the future works in its `subtle exploration of relationships against a backdrop of war`.[171] Her post-war works, which are alternately set at home and abroad, are considered first, less than successful steps in clarifying her ideas about an expatriate war and how to write about it. Novels and stories set in England and Ireland are permeated by staleness and discontent, while those set abroad highlight the excitement and adventure of her later works.[180] Two books set in Jerusalem, The Artist Among the Missing (1949) and School for Love (1951), her first commercial and critical success, are also first steps in exploring themes such war, colonialism and British imperialism.[3][165]

Manning wrote reviews, radio adaptations and scripts and several non-fiction books.[181] Her book The Remarkable Expedition (1947) about Emin Pasha and Henry Stanley was generally well reviewed,[102] and when reissued in 1985 was praised for its humour, story telling and fairness to both subjects.[101][182] Her travel book about Ireland, The Dreaming Shore (1950), received a mixed review even from her old friend Louis MacNeice,[183] but extracts from this and other of Manning`s Irish writing have subsequently been admired and anthologised.[184][185] Manning`s book Extraordinary cats (1967) proved to be chiefly about her own well-loved pets, and Stevie Smith`s review in the Sunday Times complained that the book was `more agitated than original`.[186] She also published two collections of short stories, the well-reviewed Growing Up (1946) and A Romantic Hero and Other Stories (1967); the latter included eight stories from the earlier volume, and is imbued with a sense of mortality.[187]

Themes Edit

War Edit

In contrast to other women`s war fiction of the period, Manning`s works do not recount life on the home front. Instead, her Irish and Second World War fiction observe combatants and non-combatants at the front and behind the lines.[40][165][188] Wars, in Manning`s view, are battles for place and influence, and `with her range of images and illusions, Manning reminds us that wars over land have been a constant`.[189] Her books do not celebrate British heroism nor the innocence of civilians, emphasising instead that the causes and dangers of war come as much from within as from without, with the gravest threats coming from fellow Britons.[190][191] Military men are far from heroic, and official British responses are presented as farcical.[192][193] In the Fortunes of War, the conflict is viewed largely from the perspective of a civilian woman, an observer, though later books include Simon Boulderstone`s soldier`s view of battle.[40][165] Views differ on her success in the Fortunes of War battlescenes; initial reviews by Auberon Waugh and Hugh Massie criticised them as implausible and not fully realised,[194] but later commentators have describing her depiction of battle as vivid, poignant and largely convincing.[165][169][172] Her books serve as an indictment of war and its horrors; William Gerhardie noted in 1954 of Artist among the Missing that `it is war seen in a compass so narrowed down that the lens scorches and all but ignites the paper`.[189] There is a strong focus of the impermanence of life; death and mortality are a constant presence and preoccupation for civilian and soldier alike,[169] and repetition – of stories, events and deaths – used to give `the impression of lives trapped in an endless war` for which there is no end in sight.[195]

Colonialism and imperialism Edit

A major theme of Manning`s works is the British empire in decline.[166] Her fiction contrasts deterministic, imperialistic views of history with one that accepts the possibility of change for those displaced by colonialism.[166] Manning`s works take a strong stance against British imperialism,[165] and are harshly critical of racism, anti-Semitism and oppression at the end of the British colonial era.[196][197] `British imperialism is shown to be a corrupt and self-serving system, which not only deserves to be dismantled but which is actually on the verge of being dismantled`, writes Steinberg.[198] The British characters in Manning`s novels almost all assume the legitimacy of British superiority and imperialism and struggle with their position as oppressors who are unwelcome in countries they have been brought up to believe welcome their colonising influence.[173][199] In this view, Harriet`s character, marginalised as an exile and a woman, is both oppressor and oppressed,[200] while characters such as Guy, Prince Yakimov and Sophie seek to exert various forms of power and authority over others, reflecting in microcosm the national conflicts and imperialism of the British Empire.[40][201][202] Phyllis Lassner, who has written extensively on Manning`s writing from a colonial and post-colonial perspective, notes how even sympathetic characters are not excused their complicity as colonisers; the responses of the Pringles assert `the vexed relationship between their own status as colonial exiles and that of the colonised` and native Egyptians, though given very little direct voice in The Levant Trilogy, nevertheless assert subjectivity for their country.[203]

In The Artist Among the Missing (1949), Manning illustrates the racial tensions that are created when imperialism and multiculturalism mix, and, as in her other war novels, evaluates the political bind in which the British seek to defeat racist Nazism while upholding British colonial exploitation.[204] The School for Love (1951) is the tale of an orphaned boy`s journey of disillusionment in a city that is home to Arabs, Jews and a repressive, colonial presence represented in the novel by the cold, self-righteous, and anti-Semitic character of Miss Bohun.[205]

Manning explores these themes not only in her major novels set in Europe and the Middle East, but also in her Irish fiction, The Wind Changes (1937) and eight short stories which were mostly written early in her career.[166] In these works, colonialist attitudes are reproduced by Manning`s stereotyping of Catholic southerners as wild, primitive and undisciplined, while northerners live lives of well-ordered efficiency. Displaced principal characters struggle to find their place in social groups whose values they no longer accept.[166] Manning has also been noted for her direct and early focus on the impact of the end of colonial rule. The Rain Forest (1974) presents a later, highly pessimistic view, satirising British expatriate values on a fictional island. It also critiques those involved in the independence movement, expressing a disillusioned view of the island`s future post-independence prospects.[165]

Displacement and `Otherness` Edit

Displacement and alienation are regular themes in Manning`s books. Characters are often isolated, physically and emotionally removed from family and familiar contexts and seeking a place to belong.[166][189][206] This crisis of identity may reflect that of Manning herself as the daughter of an Irish mother and a British naval officer.[166][173] `I`m really confused about what I am, never really feeling that I belong in either place`, she told an interviewer in 1969.[166] In Manning`s war fiction, conflict creates additional anxiety, emotional displacement and distance, with characters unable to communicate with each other.[40][189][207] Eve Patten notes the `pervasive sense of liminality` and the recurrent figure of the refugee in Manning`s work. Early literary interest in displacement was reinforced by Manning`s own terrifying and disorientating experiences as a refugee during the war.[87] Her travels also brought her into direct contact with the far worse plight of other war refugees, including Jewish asylum-seekers who were leaving Romania aboard the Struma.[87] Exile had its rewards for literary refugees such as Manning, offering exposure to different cultures and `the sense of a greater, past civilisation`, as she described in her 1944 review of British poetry.[87][208] Her writing reflects her deep concern for the realities of most refugees, who are portrayed as `a degraded and demoralised Other`, challenging complacent Western notions of stability and nationality.[87]

Manning has been classified as an Orientalist writer, whose depictions of cultures frequently emphasise exoticism and alien landscape.[87][170] This feature has been most closely examined in her novels set in Romania. In these, scholars note Manning`s positioning of Romania as an exotic `Other`, a legacy of the Ottoman Empire located at the limits of civilised Europe and on the frontier with the uncivilised Orient.[170][172] Her negative perceptions of Romanian `Otherness` include a childlike population living decadent lives, passive and immoral women, corruption, and a wild, untamed environment. These are contrasted with more positive reactions to Greece and Western Europe as the centre of civilising and orderly life in other books.[41][170] In keeping with colonial construction of exoticism in Western literature, `otherness` is increasingly domesticated as characters recognise, with greater exposure to the country, links to Western culture.[170] Her depiction of Romania led to Fortunes of War being restricted as seditious writing under Romania`s Communist government.[41]

Gender and feminism Edit

Manning`s books are not easily classified as a part of the feminist canon.[41][209] Manning supported the rights of women, particularly equal literary fees, but had no sympathy for the women`s movement, writing that `[t]hey make such an exhibition of themselves. None can be said to be beauties. Most have faces like porridge.`[210] In Manning`s books, the word `feminine` is used in a derogatory sense, and tends to be associated with female complacency, foolishness, artifice and deviousness,[41] and fulfilment for women comes in fairly conventional roles of wife, mother and the private domain.[190] Elizabeth Bowen remarked that Manning had `an almost masculine outfit in the way of experience` that influenced her writing about women and the war.[165] Manning viewed herself not as a female writer, but as a writer who happened to be a woman,[211] and early in her career she obscured her gender using a pseudonym and initials.[212] Manning found it easier to create male characters,[212] and in general her novels tend to minimise differences in gender, writing about people rather than women in particular.[209] Harriet Pringle, for example, moves through processes of self-discovery and empowerment as an individual rather than in feminist solidarity with her sex.[41] In Manning`s The Doves of Venus (1960), based on Manning`s friendship with Stevie Smith, female characters display `the 1950s anger more often associated ... with young men`.[165] Treglown comments on how Manning`s early books generally took a forthright approach to sex, often initiated by female characters. Her approach became more nuanced in later volumes, with a subtler depiction of sex, sensuality and sexual frustration in Fortunes of War.[41][165] The Jungian critic Richard Sugg interpreted Manning`s female characters as punishing themselves for breaching society`s gender norms, including for having erotic feelings.[213] In contrast, Treglown hypothesised that it reflected Manning`s ongoing grieving for her stillborn child.[165]

Orijentalizam edvard said todorova imaginarni balkan postkolonijalizam roman xx veka

International shipping

Paypal only

(Države Balkana: Uplata može i preko pošte ili Western Union-a)

1 euro = 117.5 din

For international buyers please see instructions below:

To buy an item: Click on the red button KUPI ODMAH

Količina: 1 / Isporuka: Pošta / Plaćanje: Tekući račun

To confirm the purchase click on the orange button: Potvrdi kupovinu (After that we will send our paypal details)

To message us for more information: Click on the blue button POŠALJI PORUKU

To see overview of all our items: Click on Svi predmeti člana

Ako je aktivirana opcija besplatna dostava, ona se odnosi samo na slanje kao preporučena tiskovina ili cc paket na teritoriji Srbije.

Poštarina za knjige je u proseku 225 dinara, u slučaju da izaberete opciju plaćanje pre slanja i slanje preko pošte. CC paket je 340 dinara. Postexpress i kurirske službe su skuplje ali imaju opciju plaćanja pouzećem. Ako nije stavljena opcija da je moguće slanje i nekom drugom kurirskom službom pored postexpressa, slobodno kupite knjigu pa nam u poruci napišite koja kurirska služba vam odgovara.

Ukoliko još uvek nemate bar 10 pozitivnih ocena, ili imate negativnih ocena, zbog nekoliko neprijatnih iskustava, molili bi vas da nam uplatite cenu kupljenog predmeta unapred.

Novi Sad lično preuzimanje (pored Kulturne stanice Eđšeg) ili svaki dan ili jednom nedeljno zavisno od lokacije prodatog predmeta (jedan deo predmeta je u Novom Sadu, drugi u kući van grada).

Našu kompletnu ponudu možete videti preko linka

https://www.kupindo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakPredmeta

Ukoliko tražite još neki naslov koji ne možete da nađete pošaljite nam poruku možda ga imamo u magacinu.

Pogledajte i našu ponudu na limundu https://www.limundo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakAukcija

Slobodno pitajte šta vas zanima preko poruka. Preuzimanje moguce u Novom Sadu i Sremskoj Mitrovici uz prethodni dogovor. (Većina knjiga je u Sremskoj Mitrovici, manji broj u Novom Sadu, tako da se najavite nekoliko dana ranije u slucaju ličnog preuzimanja, da bi knjige bile donete, a ako Vam hitno treba neka knjiga za danas ili sutra, obavezno proverite prvo preko poruke da li je u magacinu da ne bi doslo do neprijatnosti). U krajnjem slučaju mogu biti poslate i poštom u Novi Sad i stižu za jedan dan.

U Novom Sadu lično preuzimanje na Grbavici na našoj adresi ili u okolini po dogovoru. Dostava na kućnu adresu u Novom Sadu putem kurira 350 dinara.

Slanje nakon uplate na račun u Erste banci (ukoliko ne želite da plaćate po preuzimanju). Poštarina za jednu knjigu, zavisno od njene težine (do 2 kg), može biti od 170-264 din. Slanje vise knjiga u paketu težem od 2 kg 340-450 din. Za cene postexpressa ili drugih službi se možete informisati na njihovim sajtovima.

http://www.postexpress.rs/struktura/lat/cenovnik/cenovnik-unutrasnji-saobracaj.asp

INOSTRANSTVO: Šaljem po dogovoru, ili po vašim prijateljima/rodbini ili poštom. U Beč idem jednom godišnje pa ako se podudare termini knjige mogu doneti lično. Skuplje pakete mogu poslati i po nekom autobusu, molim vas ne tražite mi da šaljem autobusima knjige manje vrednosti jer mi odlazak na autobusku stanicu i čekanje prevoza pravi veći problem nego što bi koštala poštarina za slanje kao mali paket preko pošte.

Ukoliko kupujete više od jedne knjige javite se porukom možda Vam mogu dati određeni popust na neke naslove.

Sve knjige su detaljno uslikane, ako Vas još nešto interesuje slobodno pitajte porukom. Reklamacije primamo samo ukoliko nam prvo pošaljete knjigu nazad da vidim u čemu je problem pa nakon toga vraćamo novac. Jednom smo prevareni od strane člana koji nam je vratio potpuno drugu knjigu od one koju smo mu mi poslali, tako da više ne vraćamo novac pre nego što vidimo da li se radi o našoj knjizi.

Ukoliko Vam neka pošiljka ne stigne za dva ili tri dana, odmah nas kontaktirajte za broj pošiljke kako bi videli u čemu je problem. Ne čekajte da prođe više vremena, pogotovo ako ste iz inostranstva, jer nakon određenog vremena pošiljke se vraćaju pošiljaocu, tako da bi morali da platimo troškove povratka i ponovnog slanja. Potvrde o slanju čuvamo do 10 dana. U 99% slučajeva sve prolazi glatko, ali nikad se ne zna.

Ukoliko uvažimo vašu reklamaciju ne snosimo troškove poštarine, osim kada je očigledno naša greška u pitanju.

Predmet: 69170645