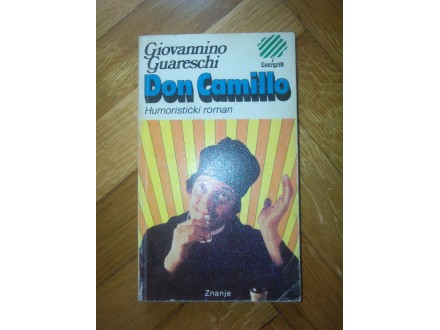

Don Camillo - Giovannino Guareschi - Don Kamilo

| Cena: |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | Pošta Post Express Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja)

Lično |

| Grad: |

Beograd-Vračar, Beograd-Vračar |

Godina izdanja: Ostalo

ISBN: Ostalo

Jezik: Srpski

Autor: Strani

Giovannino Guareschi - Don Camillo

Don Kamilo

Znanje, Zagreb, 1980.

Mek povez, 283 strane.

RETKO!

Don Camillo (pronounced [ˈdɔŋ kaˈmillo]) and Peppone (pronounced [pepˈpoːne]) are the fictional protagonists of a series of works by the Italian writer and journalist Giovannino Guareschi set in what Guareschi refers to as the `small world` of rural Italy after World War II. Most of the Don Camillo stories came out in the weekly magazine Candido, founded by Guareschi with Giovanni Mosca. These `Little World` (Italian: Piccolo Mondo) stories amounted to 347 in total and were put together and published in eight books, only the first three of which were published when Guareschi was still alive.

Don Camillo is a parish priest and is said to have been inspired by an actual Roman Catholic priest, World War II partisan and detainee at the concentration camps of Dachau and Mauthausen, named Don Camillo Valota (1912–1998).[1][2] Guareschi was also inspired by Don Alessandro Parenti, a priest of Trepalle, near the Swiss border. Peppone is the communist town mayor. The tensions between the two characters and their respective factions form the basis of the works` satirical plots.

Characterisation

Giovannino Guareschi and Fernandel on the set at Brescello

In the post-war years (after 1945), Don Camillo Tarocci (his full name, which he rarely uses) is the hotheaded priest of a small town in the Po valley in northern Italy. He is a big man, tall and strong with hard fists. For the films, the town chosen to represent that of the books was Brescello (which currently has a museum dedicated to Don Camillo and Peppone) after the production of movies based on Guareschi`s tales, but in the first story Don Camillo is introduced as the parish priest of Ponteratto.

Don Camillo talking with Jesus. He is wearing a black biretta.

Gino Cervi as Peppone

Don Camillo is constantly at odds with the Communist mayor, Giuseppe Bottazzi, better known as Peppone (meaning, roughly, `Big Joe`) and is also on very close terms with the crucifix in his town church. Through the crucifix he hears the voice of Christ.[3] The Christ in the crucifix often has far greater understanding than Don Camillo of the troubles of the people, and has to constantly but gently reprimand the priest for his impatience.

What Peppone and Camillo have in common is an interest in the well-being of the town. They also appear to have both been partisan fighters during World War II; one episode mentions Camillo having braved German patrols in order to reach Peppone and his fellow Communists in the mountains and administer Mass to them under field conditions. While Peppone makes public speeches about how `the reactionaries` ought to be shot, and Don Camillo preaches fire and brimstone against `godless Communists`, they actually grudgingly admire each other. Therefore, they sometimes end up working together in peculiar circumstances, though keeping up their squabbling. Thus, although he publicly opposes the Church as a Party duty, Peppone takes his gang to the church and baptises his children there, which makes him part of Don Camillo`s flock; also, Peppone and other Communists are seen as sharing in veneration of the Virgin Mary and local Saints. Don Camillo also never condemns Peppone himself, but the ideology of communism which is in direct opposition to the church.

Peppone and his comrades are sometimes seen at odds with the city-based Communist bureaucrats, who are sometimes seen as `barging in` and trying to dictate policy to the local Communists without knowing the local conditions. This is paralleled by Don Camillo sometimes coming into serious conflict with his Bishop, on one occasion a case of flagrant disobedience leading to Camillo being exiled to a tiny village high in the mountains; however, the Bishop is soon forced to reinstate him at the strong demand of his parishioners (including the Communists).

As depicted in the stories, the Communists are the only political party with a mass grassroots organization in the town. The Italian Christian Democratic Party, the main force in Italian politics at the time, does not have a local political organization (at least, none is ever mentioned); rather, it is the Catholic Church which unofficially but very obviously plays that role. Don Camillo thus plays an explicitly political as well as religious role. For example, when the Communists organize a local campaign to sign the Stockholm Peace Appeal, it is Don Camillo who organizes a counter-campaign, and the townspeople take for granted that such a political campaign is part of his work as priest.

Many stories are satirical and take on the real world political divide between the Italian Roman Catholic Church and the Italian Communist Party, not to mention other worldly politics. Others are tragedies about schism, politically motivated murder, and personal vendettas in a small town where everyone knows everyone else, but not everyone necessarily likes everyone else very much.

Political forces other than the Communists and the Catholics have only a marginal presence. In one episode the local Communists are incensed at the announcement that the small Italian Liberal Party has scheduled an election rally in their town, and mobilize in force to break it up—only to discover virtually no local Liberals have turned up; the Liberal speaker, a middle-aged professor, speaks to a predominantly Communist audience and wins its grudging respect by his courage and determination.

In one story, Don Camillo visits the Soviet Union, pretending to be a comrade. In another, the arrival of pop culture and motorcycles propels Don Camillo into fighting `decadence`, a struggle in which he finds he has his hands full, especially when Christ mainly smiles benevolently on the young rascals. In this later collection, Peppone is the owner of several profitable dealerships, riding the `Boom` years of the 1960s in Italy. He is no longer quite the committed Communist he once was, but he still does not get on with Don Camillo – at least not in public. Don Camillo has his own problems: the Second Vatican Council has brought changes in the Church, and a new assistant priest, who comes to be called Don Chichì, has been foisted upon him to see that Don Camillo moves with the times. Don Camillo, of course, has other ideas.

Despite their bickering, the goodness and generosity of each character can be seen during hard times. They always understand and respect each other when one is in danger, when a flood devastates the town, when death takes a loved one, and in many other situations in which the two `political enemies` show their mutual respect for one another and fight side by side for the same ideals (even if they are each conditioned by their individual public roles in society).

Guareschi created a second series of novels about a similar character, Don Candido, Archbishop of Trebilie (or Trebiglie, literally `three marble balls` or `three billiard balls`). The name of this fictional town is a play on words of Trepalle (literally `three balls`), a real town (near Livigno) whose priest was an acquaintance of Guareschi`s.

Predmet: 75452277