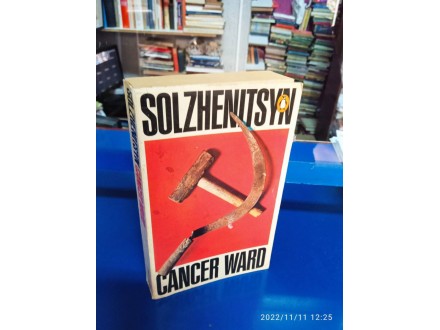

Cancer Ward by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

| Cena: |

| Želi ovaj predmet: | 2 |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | Pošta Post Express Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja)

Lično |

| Grad: |

Sombor, Sombor |

Godina izdanja: Ostalo

ISBN: Ostalo

Jezik: Engleski

Autor: Strani

Cancer Ward by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Russian author and Nobel Prize winner, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, completed his book Cancer Ward in 1966. English translations were published in 1968, and although book was banned in the Soviet Union, unauthorized Russian copies were distributed in samizdat.

The story takes place in a male cancer ward of a Soviet hospital in the mid-1950’s and revolves around a number of characters, the central one being Oleg Kostoglotov. Kostoglotov’s life mirrors that of Solzhenitsyn in that he was imprisoned for his criticism of Stalin, and after being diagnosed with stomach cancer, was transferred from the concentration camp to a cancer ward. And like Solzhenitsyn, he later recovered.

I was totally absorbed by this book’s 570 pages and despite the fact that Russian literature is often notoriously hard to read, this book definitely wasn’t.

The most fascinating aspect of Cancer Ward for me wasn’t so much the allegorical links to the Communist regime and the descriptions of life in a dictatorship. As interesting as they were, there have been other books I’ve read that addressed this, one of them also written by Solzhenitsyn. (See One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich)

What was so interesting to me was the medical treatment of cancer and the attitude of the medical staff to patients and treatment.

Kostoglotov believed that he had the right to choose what form and how much treatment he should have. The medical profession believed that information should be withheld from patients, ‘for their own good.’ They didn’t understand the technicalities and should leave the decisions to those who do. This is really no different to what used to happen in Australia, for instance. It wasn’t uncommon to leave a patient ignorant of their impending doom. Relatives could make the call on whether to let a member of their family know that their disease was terminal. Even now, to question the standard method of treatment for something like cancer is to bring down the ire of the establishment upon yourself, as a friend of mine recently found out when she decided not to undergo chemotherapy after her cancer surgery.

The medical staff in that Russian hospital were conscientious and sincere and believed they were doing the right thing by Kostoglotov. They were tight-lipped about the hormonal therapy he was receiving and its long-term effect of impotency, but he didn’t want to be saved ‘at any price.’

Kostoglotov also did some of his own research and discovered that concern was beginning to surface in medical circles regarding the long term effects of radiotherapy.

‘The gist of it was that X-ray cures, which had been safely, successfully, even brilliantly accomplished ten or fifteen years ago through heavy doses of radiation, were now resulting in unexpected damage or mutilation of the irradiated parts.

…ten, fifteen or eighteen years ago when the term ‘radiation sickness’ did not exist, X-ray radiation had seemed such a straightforward, reliable and foolproof method, such a magnificent achievement of modern medical technique, that it was considered retrograde, almost sabotage of public health, to refuse to use it and to look for other, parallel or round-about methods.’

Solzhenitsyn explores the relationship between doctors and patients and between fellow cancer sufferers as they go through their various forms of treatment.

There are numerous Translator’s notes throughout the book that explain some of the historical background needed to understand the context of the author’s writing, such as this:

Khrushchev had just become Party leader. He believed that wide cultivation of maize in the north of Russia would solve grain and fodder problems. He called upon Young Communists to fight those who didn’t believe maize could be grown there. His scheme, however, was defeated by the climate.

Although Solzhenitsyn insisted that his book was simply about cancer, there are seemingly allegorical statements that contradict this:

A man dies from a tumour, so how can a country survive with growths like labour camps and exiles?

I highly recommend this book, especially if you have some sort of medical background. Solzhenitsyn was perceptive and prophetic and his insights into human nature were superb.

Some favourite passages:

It is not our level of prosperity that makes for happiness but the kinship of heart to heart and the way we look at the world. Both attitudes lie within our power, so that a man is happy so long as he chooses to be happy, and no one can stop him.

Nowadays we don’t think much of a man’s love for an animal; we laugh at people who are attached to cats. But if we stop loving animals, aren’t we bound to stop loving humans too?

Soon it will be summer, and this summer I want to sleep on a camp-bed under the stars, to wake up at night and know by the positions of Cygnus and Pegasus what time it is, to live just this one summer and see the stars without their being blotted out by camp searchlights- then afterwards I would be quite content never to wake again.

As the two-thousand-year-old saying goes, you can have eyes and still not see.

But a hard life improves the vision. There were some in the wing who immediately recognized each other for what they were…It was as if they bore some luminous sign on their foreheads, or stigmata on their feet and palms…The Uzbeks and the Karakalpaks had no difficulty in recognising their own people in the clinic, nor did those who had once lived in the shadow of the barbed wire.

The Penguin translation I read was first published by The Bodley Head in 1968.

HOD. D 1.

Ne šaljem INOSTRANSTVO od nedavno knjige idu na carinu.

Predmet: 72835997