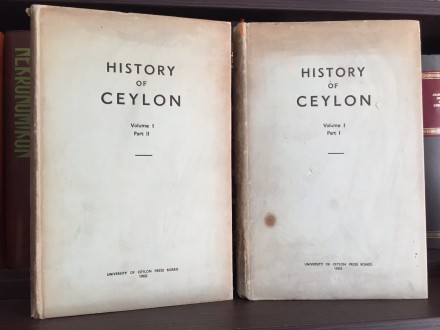

HISTORY OF CEYLON 1-2 (1960)

| Cena: |

| Želi ovaj predmet: | 7 |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | BEX Pošta DExpress Post Express Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja) Ostalo (pre slanja) Pouzećem Lično |

| Grad: |

Novi Sad, Novi Sad |

ISBN: Ostalo

Godina izdanja: .

Jezik: Engleski

Autor: Strani

Lepo očuvano

Kao na slikama

Retko!

1960.

University of Ceylon Press Board

Istorija Cejlona / Šri Lanke

Rare books

The history of Sri Lanka is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The early human remains found on the island of Sri Lanka date to about 38,000 years ago (Balangoda Man).

The historical period begins roughly in the 3rd century, based on Pali chronicles like the Mahavamsa, Deepavamsa, and the Culavamsa. They describe the history since the arrival of Prince Vijaya from Northern India[1][2][3][4] The earliest documents of settlement in the Island are found in these chronicles. These chronicles cover the period since the establishment of the Kingdom of Tambapanni in the 6th century BCE by the earliest ancestors of the Sinhalese. The first Sri Lankan ruler of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, Pandukabhaya, is recorded for the 4th century BCE. Buddhism was introduced in the 3rd century BCE by Arhath Mahinda (son of the Indian emperor Ashoka).

The island was divided into numerous kingdoms over the following centuries, intermittently (between CE 993–1077) united under Chola rule. Sri Lanka was ruled by 181 monarchs from the Anuradhapura to Kandy periods.[5][unreliable source?] From the 16th century, some coastal areas of the country were also controlled by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. Between 1597 and 1658, a substantial part of the island was under Portuguese rule. The Portuguese lost their possessions in Ceylon due to Dutch intervention in the Eighty Years` War. Following the Kandyan Wars, the island was united under British rule in 1815. Armed uprisings against the British took place in 1818 Uva Rebellion and 1848 Matale Rebellion. Independence was finally granted in 1948 but the country remained a Dominion of the British Empire until 1972.

In 1972, Sri Lanka assumed the status of a Republic. A constitution was introduced in 1978 which made the Executive President the head of state. The Sri Lankan Civil War began in 1983, including Insurrections in 1971 and 1987, with the 25-year-long civil war ending in 2009. There was an attempted coup in 1962 against the government under Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

Prehistory[edit]

Main article: Prehistory of Sri Lanka

Evidence of human colonization in Sri Lanka appears at the site of Balangoda. Balangoda Man arrived on the island about 125,000 years ago and has been identified as Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who lived in caves. Several of these caves, including the well-known Batadombalena and the Fa Hien Cave, have yielded many artifacts from these people, who are currently the first known inhabitants of the island.

Balangoda Man probably created Horton Plains, in the central hills, by burning the trees in order to catch game. However, the discovery of oats and barley on the plains at about 15,000 BCE suggests that agriculture had already developed at this early date.[6]

Several minute granite tools (about 4 centimetres in length), earthenware, remnants of charred timber, and clay burial pots date to the Mesolithic. Human remains dating to 6000 BCE have been discovered during recent excavations around a cave at Warana Raja Maha Vihara and in the Kalatuwawa area.

Cinnamon is native to Sri Lanka and has been found in Ancient Egypt as early as 1500 BCE, suggesting early trade between Egypt and the island`s inhabitants. It is possible that Biblical Tarshish was located on the island. James Emerson Tennent identified Tarshish with Galle.[7]

The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1200 BCE, if not earlier (Possehl 1990; Deraniyagala 1992:734). The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon-dated to c. 1000–800 BCE at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya (Deraniyagala 1992:709-29; Karunaratne and Adikari 1994:58; Mogren 1994:39; with the Anuradhapura dating corroborated by Coningham 1999). It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.[8]

During the protohistoric period (1000-500 BCE) Sri Lanka was culturally united with southern India.,[9] and shared the same megalithic burials, pottery, iron technology, farming techniques and megalithic graffiti.[10][11] This cultural complex spread from southern India along with Dravidian clans such as the Velir, prior to the migration of Prakrit speakers.[12][13][10]

Archaeological evidence for the beginnings of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka is found at Anuradhapura, where a large city–settlement was founded before 900 BCE. The settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE, but by 700 BCE it had expanded to 50 hectares.[14] A similar site from the same period has also been discovered near Aligala in Sigiriya.[15]

The hunter-gatherer people known as the Wanniyala-Aetto or Veddas, who still live in the central, Uva and north-eastern parts of the island, are probably direct descendants of the first inhabitants, Balangoda Man. They may have migrated to the island from the mainland around the time humans spread from Africa to the Indian subcontinent.

Later Indo Aryan migrants developed a unique hydraulic civilization named Sinhala. Their Achievements include the construction of the largest reservoirs and dams of the ancient world as well as enormous pyramid-like stupa (dāgaba in Sinhala) architecture. This phase of Sri Lankan culture may have seen the introduction of early Buddhism.[16]

Early history recorded in Buddhist scriptures refers to three visits by the Buddha to the island to see the Naga Kings, snakes that can take the form of a human at will.[17]

The earliest surviving chronicles from the island, the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, say that Yakkhas, Nagas, Rakkhas and Devas inhabited the island prior to the migration of Indo Aryans.

Pre-Anuradhapura period (543–377 BCE)[edit]

Main article: Early kingdoms period

Indo-Aryan syncretism[edit]

Main article: Prince Vijaya

The Pali chronicles, the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Thupavamsa and the Chulavamsa, as well as a large collection of stone inscriptions,[18] the Indian Epigraphical records, the Burmese versions of the chronicles etc., provide information on the history of Sri Lanka from about the 6th century BCE.[19]

The Mahavamsa, written around 400 CE by the monk Mahanama, using the Deepavamsa, the Attakatha and other written sources available to him, correlates well with Indian histories of the period. Indeed, Emperor Ashoka`s reign is recorded in the Mahavamsa. The Mahavamsa account of the period prior to Asoka`s coronation, 218 years after the Buddha`s death, seems to be part legend. Proper historical records begin with the arrival of Vijaya and his 700 followers from Vanga. A detailed description of the dynastic accounts from Vijaya`s time is provided in the Mahavamsa.[20] H. W. Codrington puts it, `It is possible and even probable that Vijaya (`The Conqueror`) himself is a composite character combining in his person...two conquests` of ancient Sri Lanka. Vijaya is an Indian prince, the eldest son of King Sinhabahu (`Man with Lion arms`) and his sister Queen Sinhasivali. Both these Sinhalese leaders were born of a mythical union between a lion and a human princess. The Mahavamsa states that Vijaya landed on the same day as the death of the Buddha (See Geiger`s preface to Mahavamsa). The story of Vijaya and Kuveni (the local reigning queen) is reminiscent of Greek legend and may have a common source in ancient Proto-Indo-European folk tales.

According to the Mahavamsa, Vijaya landed on Sri Lanka near Mahathitha (Manthota or Mannar[21]), and named[22] on the island of Tambaparni (`copper-colored sand`). This name is attested to in Ptolemy`s map of the ancient world. The Mahavamsa also describes the Buddha visiting Sri Lanka three times. Firstly, to stop a war between a Naga king and his son in law who were fighting over a ruby chair. It is said that on his last visit he left his foot mark on Siri Pada (`Adam`s Peak`).

Tamirabharani is the old name for the second longest river in Sri Lanka (known as Malwatu Oya in Sinhala and Aruvi Aru in Tamil). This river was a main supply route connecting the capital, Anuradhapura, to Mahathitha (now Mannar). The waterway was used by Greek and Chinese ships traveling the southern Silk Route.

Mahathir was an ancient port linking Sri Lanka to India and the Persian Gulf.[23]

The present day Sinhalese are a mixture of the Indo Aryans and the Indigenous[24] The Sinhalese are recognized as a distinct ethnic group from other groups in neighboring south India based on the Indo-Aryan language, culture, Theravada Buddhism, genetics and the physical anthropology.

Anuradhapura period (377 BCE–1017)[edit]

Main articles: Anuradhapura period and Anuradhapura Kingdom

Pandyan Kingdom coin depicting a temple between hill symbols and elephant, Pandyas, Sri Lanka, 1st century CE.

In the early ages of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, the economy was based on farming and early settlements were mainly made near the rivers of the east, north central, and north east areas which had the water necessary for farming the whole year round. The king was the ruler of country and responsible for the law, the army, and being the protector of faith. Devanampiya Tissa (250–210 BCE) was Sinhalese and was friends with the King of the Maurya clan. His links with Emperor Asoka led to the introduction of Buddhism by Mahinda (son of Asoka) around 247 BCE. Sangamitta (sister of Mahinda) brought a Bodhi sapling via Jambukola (west of Kankesanthurai). This king`s reign was crucial to Theravada Buddhism and for Sri Lanka.

The Mauryan-Sanskrit text Arthashastra referred to the pearls and gems of Sri Lanka. A kind of pearl, kauleya (Sanskrit: कौलेय) was referred in that text and also mentioned it collected from Mayurgrām of Sinhala. Pārsamudra(पारसमुद्र), a gem, was also being collected from Sinhala.[25]

Ellalan (205–161 BCE) was a Tamil King who ruled `Pihiti Rata` (Sri Lanka north of the Mahaweli) after killing King Asela. During Ellalan`s time Kelani Tissa was a sub-king of Maya Rata (in the south-west) and Kavan Tissa was a regional sub-king of Ruhuna (in the south-east). Kavan Tissa built Tissa Maha Vihara, Dighavapi Tank and many shrines in Seruvila. Dutugemunu (161–137 BCE), the eldest son of King Kavan Tissa, at 25 years of age defeated the South Indian Tamil invader Elara (over 64 years of age) in single combat, described in the Mahavamsa. The Ruwanwelisaya, built by Dutugemunu, is a dagaba of pyramid-like proportions and was considered an engineering marvel.[citation needed]

Pulahatta (or Pulahatha), the first of the Five Dravidians, was deposed by Bahiya. He in turn was deposed by Panaya Mara who was deposed by Pilaya Mara, murdered by Dathika in 88 BCE. Mara was deposed by Valagamba I (89–77 BCE) which ended Tamil rule. The Mahavihara Theravada Abhayagiri (`pro-Mahayana`) doctrinal disputes arose at this time. The Tripitaka was written in Pali at Aluvihara, Matale. Chora Naga (63–51 BCE), a Mahanagan, was poisoned by his consort Anula who became queen. Queen Anula (48–44 BCE), the widow of Chora Naga and of Kuda Tissa, was the first Queen of Lanka. She had many lovers who were poisoned by her and was killed by Kuttakanna Tissa. Vasabha (67–111 CE), named on the Vallipuram gold plate, fortified Anuradhapura and built eleven tanks as well as pronouncing many edicts. Gajabahu I (114–136) invaded the Chola kingdom and brought back captives as well as recovering the relic of the tooth of the Buddha. A Sangam Period classic, Manimekalai, attributes the origin of the first Pallava King from a liaison between the daughter of a Naga king of Manipallava named Pilli Valai (Pilivalai) with a Chola king, Killivalavan, out of which union was born a prince, who was lost in ship wreck and found with a twig (pallava) of Cephalandra Indica (Tondai) around his ankle and hence named Tondai-man. Another version states `Pallava` was born from the union of the Brahmin Ashvatthama with a Naga Princess also supposedly supported in the sixth verse of the Bahur plates which states `From Ashvatthama was born the king named Pallava`.[26]

Sri Lankan imitations of 4th-century Roman coins, 4th to 8th centuries.

Ambassador from Sri Lanka (獅子國 Shiziguo) to China (Liang dynasty), Wanghuitu (王会图), circa 650 CE

There was intense Roman trade with the ancient Tamil country (present day Southern India) and Sri Lanka,[27] establishing trading settlements which remained long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[28]

It was in the first century AD where Saint Thomas the Apostle introduced Sri Lanka`s first monotheistic religion, Christianity, according to a local Christian tradition[29]

During the reign of Mahasena (274–301) the Theravada (Maha Vihara) was persecuted and the Mahayanan branch of Buddhism appeared. Later the King returned to the Maha Vihara. Pandu (429) was the first of seven Pandiyan rulers, ending with Pithya in 455. Dhatusena (459–477) `Kalaweva` and his son Kashyapa (477–495) built the famous Sigiriya rock palace where some 700 rock graffiti give a glimpse of ancient Sinhala.

Decline

Main article: Chola occupation of Anuradhapura

In 993, when Raja Raja Chola sent a large Chola army which conquered the Anuradhapura Kingdom, in the north, and added it to the sovereignty of the Chola Empire.[30] The whole island was subsequently conquered and incorporated as a province of the vast Chola empire during the reign of his son Rajendra Chola.[31][32][33][34]

Polonnaruwa period (1056–1232)[edit]

Main articles: Polonnaruwa period and Kingdom of Polonnaruwa

The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was the second major Sinhalese kingdom of Sri Lanka. It lasted from 1055 under Vijayabahu I to 1212 under the rule of Lilavati. The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa came into being after the Anuradhapura Kingdom was invaded by Chola forces under Rajaraja I and led to formation of the Kingdom of Ruhuna, where the Sinhalese Kings ruled during Chola occupation.

Decline

Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I invaded Sri Lanka in the 13th century and defeated Chandrabanu the usurper of the Jaffna Kingdom in northern Sri Lanka.[35] Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I forced Candrabhanu to submit to the Pandyan rule and to pay tributes to the Pandyan Dynasty. But later on when Candrabhanu became powerful enough he again invaded the Singhalese kingdom but he was defeated by the brother of Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I called Veera Pandyan I and Candrabhanu died.[35] Sri Lanka was invaded for the 3rd time by the Pandyan Dynasty under the leadership of Arya Cakravarti who established the Jaffna kingdom.[35]

Transitional period (1232–1505)[edit]

Ptolemic map of Ceylon (1482)

Jaffna Kingdom[edit]

Main article: Jaffna kingdom

Also known as the Aryacakravarti dynasty, was a northern kingdom centred around the Jaffna Peninsula.[36]

In 1247, the Malay kingdom of Tambralinga which was a vassal of the Srivijaya Empire led by their king Chandrabhanu[37] briefly invaded Sri Lanka especially the Jaffna Kingdom, from Insular Southeast Asia. They were then expelled by the South Indian Pandyan Dynasty.[38] However, this temporary invasion permanently introduced the presence of various Malayo-Polynesian merchant ethnic groups, from Sumatrans (Indonesia) to Lucoes (Philippines) into Sri Lanka.[39]

Kingdom of Dambadeniya[edit]

Main article: Kingdom of Dambadeniya

After defeating Kalinga Magha, King Parakramabahu established his Kingdom in Dambadeniya. He built the Temple of The Sacred Tooth Relic in Dambadeniya.

Kingdom of Gampola[edit]

Main article: Kingdom of Gampola

It was established by king Buwanekabahu IV, he is said to be the son of Sawulu Vijayabahu. During this time, a Muslim traveller and geographer named Ibn Battuta came to Sri Lanka and wrote a book about it. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya is the main building made in the Gampola Kingdom period. The Lankatilaka Viharaya is also a main building built in Gampola.

Kingdom of Kotte[edit]

Main article: Kingdom of Kotte

After winning the battle, Parakramabahu VI sent an officer named Alagakkonar to check the new kingdom of Kotte.

Kingdom of Sitawaka[edit]

Main article: Kingdom of Sitawaka

The kingdom of Sithawaka lasted for a short span of time during the Portuguese era.

Vannimai[edit]

Main article: Vanni Nadu

Vannimai, also called Vanni Nadu, were feudal land divisions ruled by Vanniar chiefs south of the Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka. Pandara Vanniyan allied with the Kandy Nayakars led a rebellion against the British and Dutch colonial powers in Sri Lanka in 1802. He was able to liberate Mullaitivu and other parts of northern Vanni from Dutch rule. In 1803, Pandara Vanniyan was defeated by the British and Vanni came under British rule.[40]

Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1505–1594)[edit]

Portuguese intervention[edit]

Main articles: Portuguese Ceylon and Sinhalese–Portuguese War

A Portuguese (later Dutch) fort in Batticaloa, Eastern Province built in the 16th century.

The first Europeans to visit Sri Lanka in modern times were the Portuguese: Lourenço de Almeida arrived in 1505 and found that the island, divided into seven warring kingdoms, was unable to fend off intruders. The Portuguese founded a fort at the port city of Colombo in 1517 and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas. In 1592, the Sinhalese moved their capital to the inland city of Kandy, a location more secure against attack from invaders. Intermittent warfare continued through the 16th century.

Many lowland Sinhalese converted to Christianity due to missionary campaigns by the Portuguese while the coastal Moors were religiously persecuted and forced to retreat to the Central highlands. The Buddhist majority disliked the Portuguese occupation and its influences, welcoming any power who might rescue them. When the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen landed in 1602, the king of Kandy appealed to him for help.[41]

Dutch intervention[edit]

Main article: Dutch Ceylon

Rajasinghe II, the king of Kandy, made a treaty with the Dutch in 1638 to get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas of the island. The main conditions of the treaty were that the Dutch were to hand over the coastal areas they had captured to the Kandyan king in return for a Dutch trade monopoly over the island. The agreement was breached by both parties. The Dutch captured Colombo in 1656 and the last Portuguese strongholds near Jaffnapatnam in 1658. By 1660 they controlled the whole island except the land-locked kingdom of Kandy. The Dutch (Protestants) persecuted the Catholics and the remaining Portuguese settlers but left Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims alone. The Dutch levied far heavier taxes on the people than the Portuguese had done.[41]

Kandyan period (1594–1815)[edit]

Main article: Kingdom of Kandy

On the top: illustration from Delineatio characterum quorundam incognitorum, quos in insula Ceylano spectandos praebet tumulus quidam sepulchralis published in Acta Eruditorum, 1733

After the invasion of the Portuguese, Konappu Bandara (King Vimaladharmasuriya) intelligently won the battle and became the first king of the kingdom of Kandy. He built The Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. The monarch ended with the death of the last king, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha in 1832.[42]

Colonial Sri Lanka (1815–1948)[edit]

Main articles: History of British Ceylon and British Ceylon

Late 19th-century German map of Ceylon.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796. In 1802, the Treaty of Amiens formally ceded the Dutch part of the island to Britain and it became a crown colony. In 1803, the British invaded the Kingdom of Kandy in the first Kandyan War, but were repulsed. In 1815 Kandy was annexed in the second Kandyan War, finally ending Sri Lankan independence.

Following the suppression of the Uva Rebellion the Kandyan peasantry were stripped of their lands by the Crown Lands (Encroachments) Ordinance No. 12 of 1840 (sometimes called the Crown Lands Ordinance or the Waste Lands Ordinance),[43] a modern enclosure movement, and reduced to penury. The British found that the uplands of Sri Lanka were very suitable for coffee, tea and rubber cultivation. By the mid-19th century, Ceylon tea had become a staple of the British market bringing great wealth to a small number of European tea planters. The planters imported large numbers of Tamil workers as indentured labourers from south India to work the estates, who soon made up 10% of the island`s population.[44]

The British colonial administration favoured the semi-European Burghers, certain high-caste Sinhalese and the Tamils who were mainly concentrated to the north of the country. Nevertheless, the British also introduced democratic elements to Sri Lanka for the first time in its history and the Burghers were given degree of self-government as early as 1833. It was not until 1909 that constitutional development began, with a partly elected assembly, and not until 1920 that elected members outnumbered official appointees. Universal suffrage was introduced in 1931 over the protests of the Sinhalese, Tamil and Burgher elite who objected to the common people being allowed to vote.[44]

Sorting tea in Ceylon in the 1880s

Independence movement[edit]

Main article: Sri Lankan independence movement

Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was founded to agitate for greater autonomy, although the party was soon split along ethnic and caste lines. Historian K. M. de Silva has stated that the refusal of the Ceylon Tamils to accept minority status is one of the main causes of the break up of the Ceylon National congress. The CNC did not seek independence (or `Swaraj`). What may be called the independence movement broke into two streams: the `constitutionalists`, who sought independence by gradual modification of the status of Ceylon; and the more radical groups associated with the Colombo Youth League, Labour movement of Goonasinghe, and the Jaffna Youth Congress. These organizations were the first to raise the cry of `Swaraj` (`outright independence`) following the Indian example when Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu and other Indian leaders visited Ceylon in 1926.[45] The efforts of the constitutionalists led to the arrival of the Donoughmore Commission reforms in 1931 and the Soulbury Commission recommendations, which essentially upheld the 1944 draft constitution of the Board of ministers headed by D. S. Senanayake.[45] The Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), which grew out of the Youth Leagues in 1935, made the demand for outright independence a cornerstone of their policy.[46] Its deputies in the State Council, N.M. Perera and Philip Gunawardena, were aided in this struggle by other less radical members like Colvin R. De Silva, Leslie Goonewardene, Vivienne Goonewardene, Edmund Samarkody and Natesa Iyer. They also demanded the replacement of English as the official language by Sinhala and Tamil. The Marxist groups were a tiny minority and yet their movement was viewed with great interest by the British administration. The ineffective attempts to rouse the public against the British Raj in revolt would have led to certain bloodshed and a delay in independence. British state papers released in the 1950s show that the Marxist movement had a very negative impact on the policy makers at the Colonial office.[44]

The Soulbury Commission was the most important result of the agitation for constitutional reform in the 1930s. The Tamil organization was by then led by G. G. Ponnambalam, who had rejected the `Ceylonese identity`.[47] Ponnamblam had declared himself a `proud Dravidian` and proclaimed an independent identity for the Tamils. He attacked the Sinhalese and criticized their historical chronicle known as the Mahavamsa. The first Sinhalese-Tamil riot came in 1939.[45][48] Ponnambalam opposed universal franchise, supported the caste system, and claimed that the protection of minority rights requires that minorities (35% of the population in 1931) having an equal number of seats in parliament to that of the Sinhalese (65% of the population). This `50-50` or `balanced representation` policy became the hall mark of Tamil politics of the time. Ponnambalam also accused the British of having established colonization in `traditional Tamil areas`, and having favoured the Buddhists by the Buddhist temporalities act. The Soulbury Commission rejected the submissions by Ponnambalam and even criticized what they described as their unacceptable communal character. Sinhalese writers pointed to the large immigration of Tamils to the southern urban centres, especially after the opening of the Jaffna-Colombo railway. Meanwhile, Senanayake, Baron Jayatilleke, Oliver Gunatilleke and others lobbied the Soulbury Commission without confronting them officially. The unofficial submissions contained what was to later become the draft constitution of 1944.[45]

The close collaboration of the D. S. Senanayake government with the war-time British administration led to the support of Lord Louis Mountbatten. His dispatches and a telegram to the Colonial office supporting Independence for Ceylon have been cited by historians as having helped the Senanayake government to secure the independence of Sri Lanka. The shrewd cooperation with the British as well as diverting the needs of the war market to Ceylonese markets as a supply point, managed by Oliver Goonatilleke, also led to a very favourable fiscal situation for the newly independent government.[44]

The Second World War[edit]

Main article: Ceylon in World War II

Sri Lanka was a front-line British base against the Japanese during World War II. Sri Lankan opposition to the war led by the Marxist organizations and the leaders of the LSSP pro-independence group were arrested by the Colonial authorities. On 5 April 1942, the Indian Ocean raid saw the Japanese Navy bomb Colombo. The Japanese attack led to the flight of Indian merchants, dominant in the Colombo commercial sector, which removed a major political problem facing the Senanayake government.[45] Marxist leaders also escaped to India where they participated in the independence struggle there. The movement in Ceylon was minuscule, limited to the English-educated intelligentsia and trade unions, mainly in the urban centres. These groups were led by Robert Gunawardena, Philip`s brother. In stark contrast to this `heroic` but ineffective approach to the war, the Senanayake government took advantage to further its rapport with the commanding elite. Ceylon became crucial to the British Empire in the war, with Lord Louis Mountbatten using Colombo as his headquarters for the Eastern Theatre. Oliver Goonatilleka successfully exploited the markets for the country`s rubber and other agricultural products to replenish the treasury. Nonetheless, the Sinhalese continued to push for independence and the Sinhalese sovereignty, using the opportunities offered by the war, pushed to establish a special relationship with Britain.[44]

Meanwhile, the Marxists, identifying the war as an imperialist sideshow and desiring a proletarian revolution, chose a path of agitation disproportionate to their negligible combat strength and diametrically opposed to the `constitutionalist` approach of Senanayake and other ethnic Sinhalese leaders. A small garrison on the Cocos Islands manned by Ceylonese mutinied against British rule. It has been claimed that the LSSP had some hand in the action, though this is far from clear. Three of the participants were the only British colony subjects to be shot for mutiny during World War II.[49] Two members of the Governing Party, Junius Richard Jayawardene and Dudley Senanayake, held discussions with the Japanese to collaborate in fighting the British. Sri Lankans in Singapore and Malaysia formed the `Lanka Regiment` of the anti-British Indian National Army.[44]

The constitutionalists led by D. S. Senanayake succeeded in winning independence. The Soulbury constitution was essentially what Senanayake`s board of ministers had drafted in 1944. The promise of Dominion status and independence itself had been given by the Colonial Office.

Independence[edit]

The Sinhalese leader Don Stephen Senanayake left the CNC on the issue of independence, disagreeing with the revised aim of `the achieving of freedom`, although his real reasons were more subtle.[50] He subsequently formed the United National Party (UNP) in 1946,[51] when a new constitution was agreed on, based on the behind-the-curtain lobbying of the Soulbury commission. At the elections of 1947, the UNP won a minority of seats in parliament, but cobbled together a coalition with the Sinhala Maha Sabha party of Solomon Bandaranaike and the Tamil Congress of G.G. Ponnambalam. The successful inclusions of the Tamil-communalist leader Ponnambalam, and his Sinhalese counterpart Bandaranaike were a remarkable political balancing act by Senanayake. The vacuum in Tamil Nationalist politics, created by Ponnamblam`s transition to a moderate, opened the field for the Tamil Arasu Kachchi (`Federal party`), a Tamil sovereignty party led by S. J. V. Chelvanaykam who was the lawyer son of a Christian minister.[44]

Tags: sri lanka hinduizam budizam cedomil veljačić kulture istoka

International shipping

Paypal only

(Države Balkana: Uplata može i preko pošte ili Western Union-a)

1 euro = 117.5 din

For international buyers please see instructions below:

To buy an item: Click on the red button KUPI ODMAH

Količina: 1 / Isporuka: Pošta / Plaćanje: Tekući račun

To confirm the purchase click on the orange button: Potvrdi kupovinu (After that we will send our paypal details)

To message us for more information: Click on the blue button POŠALJI PORUKU

To see overview of all our items: Click on Svi predmeti člana

Ako je aktivirana opcija besplatna dostava, ona se odnosi samo na slanje kao preporučena tiskovina ili cc paket na teritoriji Srbije.

Poštarina za knjige je u proseku 133-200 dinara, u slučaju da izaberete opciju plaćanje pre slanja i slanje preko pošte. Postexpress i kurirske službe su skuplje ali imaju opciju plaćanja pouzećem. Ako nije stavljena opcija da je moguće slanje i nekom drugom kurirskom službom pored postexpressa, slobodno kupite knjigu pa nam u poruci napišite koja kurirska služba vam odgovara.

Ukoliko još uvek nemate bar 10 pozitivnih ocena, zbog nekoliko neprijatnih iskustava, molili bi vas da nam uplatite cenu kupljenog predmeta unapred.

Novi Sad lično preuzimanje ili svaki dan ili jednom nedeljno zavisno od lokacije prodatog predmeta.

Našu kompletnu ponudu možete videti preko linka

https://www.kupindo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakPredmeta

Ukoliko tražite još neki naslov koji ne možete da nađete pošaljite nam poruku možda ga imamo u magacinu.

Pogledajte i našu ponudu na limundu https://www.limundo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakAukcija

Slobodno pitajte šta vas zanima preko poruka. Preuzimanje moguce u Novom Sadu i Sremskoj Mitrovici uz prethodni dogovor. (Većina knjiga je u Sremskoj Mitrovici, manji broj u Novom Sadu, tako da se najavite nekoliko dana ranije u slucaju ličnog preuzimanja, da bi knjige bile donete, a ako Vam hitno treba neka knjiga za danas ili sutra, obavezno proverite prvo preko poruke da li je u magacinu da ne bi doslo do neprijatnosti). U krajnjem slučaju mogu biti poslate i poštom u Novi Sad i stižu za jedan dan.

U Novom Sadu lično preuzimanje na Grbavici na našoj adresi ili u okolini po dogovoru. Dostava na kućnu adresu u Novom Sadu putem kurira 350 dinara.

Slanje nakon uplate na račun u Erste banci (ukoliko ne želite da plaćate po preuzimanju). Poštarina za jednu knjigu, zavisno od njene težine (do 2 kg), može biti od 170-264 din. Slanje vise knjiga u paketu težem od 2 kg 340-450 din. Za cene postexpressa ili drugih službi se možete informisati na njihovim sajtovima.

http://www.postexpress.rs/struktura/lat/cenovnik/cenovnik-unutrasnji-saobracaj.asp

INOSTRANSTVO: Šaljem po dogovoru, ili po vašim prijateljima/rodbini ili poštom. U Beč idem jednom godišnje pa ako se podudare termini knjige mogu doneti lično. Skuplje pakete mogu poslati i po nekom autobusu, molim vas ne tražite mi da šaljem autobusima knjige manje vrednosti jer mi odlazak na autobusku stanicu i čekanje prevoza pravi veći problem nego što bi koštala poštarina za slanje kao mali paket preko pošte.

Ukoliko kupujete više od jedne knjige javite se porukom možda Vam mogu dati određeni popust na neke naslove.

Sve knjige su detaljno uslikane, ako Vas još nešto interesuje slobodno pitajte porukom. Reklamacije primamo samo ukoliko nam prvo pošaljete knjigu nazad da vidim u čemu je problem pa nakon toga vraćamo novac. Jednom smo prevareni od strane člana koji nam je vratio potpuno drugu knjigu od one koju smo mu mi poslali, tako da više ne vraćamo novac pre nego što vidimo da li se radi o našoj knjizi.

Ukoliko Vam neka pošiljka ne stigne za dva ili tri dana, odmah nas kontaktirajte za broj pošiljke kako bi videli u čemu je problem. Ne čekajte da prođe više vremena, pogotovo ako ste iz inostranstva, jer nakon određenog vremena pošiljke se vraćaju pošiljaocu, tako da bi morali da platimo troškove povratka i ponovnog slanja. Potvrde o slanju čuvamo do 10 dana. U 99% slučajeva sve prolazi glatko, ali nikad se ne zna.

Ukoliko uvažimo vašu reklamaciju ne snosimo troškove poštarine, osim kada je očigledno naša greška u pitanju.

Predmet: 74863737