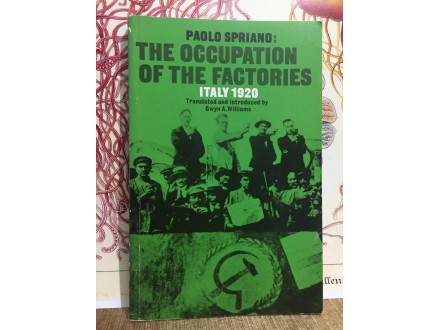

THE OCCUPATION OF THE FACTORIES (Italy 1920)

| Cena: |

| Želi ovaj predmet: | 7 |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | BEX Pošta DExpress Post Express Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja) Ostalo (pre slanja) Pouzećem Lično |

| Grad: |

Novi Sad, Novi Sad |

ISBN: Ostalo

Godina izdanja: .

Jezik: Engleski

Autor: Strani

Odlično očuvano

Paolo Spriano

The story of the mass wave of strikes and factory occupations which swept Italy 1920-21 told from the documents and accounts of the time. Written in 1964 and translated into English in 1975 by Gwyn A Williams, who also wrote the introduction.

DURING the month of September, 1920, a widespread occupation of Italian factories by their workforces took place, which originated in the auto factories, steel mills and machine tool plants of the metal sector but spread out into many other industries — cotton mills and hosiery firms, lignite mines, tire factories, breweries and distilleries, and steamships and warehouses in the port towns.

But this was not a sit-down strike; the workers continued production with their own in-plant organization. And railway workers, in open defiance of the management of the state-owned railways, shunted freight cars between the factories to enable production to continue. At its height about 600,000 workers were involved.

This movement blew up out of a conventional trade union struggle over wages. But the wage demands were only the official occasion for the fight; the real aspirations and desires that motivated the workers involved in this struggle go much deeper.[1]

Growing Disaffection with the Union Leadership

Amongst the bulk of the Italian populace at the end of World War I, whether workers in factories in the big northern cities, wage laborers on commercial farms in the northern valleys, or peasant farmers in the southern part of the country, there was a mood of expectancy, that maybe now was the time when there would be a qualitative improvement in their lives, after the upheavals and deprivation of the war years.

However, a growing aspiration for workers control, and for social transformation in an anti-capitalist direction, ran head on into the growing bureaucratization of official Italian trade-unionism.

The main trade union federation in Italy was the General Confederation of Labor (CGL), officially aligned with the Italian Socialist Party[2]. Ludovico D’Aragona, and other leaders of the CGL, looked to the British Labor Party as their model, where a professional trade union and parliamentary leadership presided over gradual reforms and an accepted institutional existence within the prevailing capitalist society.

Unlike the United States, where unionism did not become entrenched in the big industrial enterprises until the ‘30s, in Italy the unions affiliated to the CGL had already achieved contracts with major companies like Pirelli and Fiat before World War I. A professional union hierarchy had emerged, as permanent “representatives” of workers in regular bargaining with employers.

The process of union bureaucratization, and an increasing gap between the leadership and the rank-and-file, was accelerated by the First World War. During the war Italian industry was subjected to a kind of industrial feudalism with workers tied to their jobs under threat of imprisonment.

A system of joint labor/management grievance committees were imposed by the government — essentially a system of compulsory arbitration to settle disputes over wages and safety. In order to not be completely frozen out, the union officials participated on these committees. But the unions were unable to defend their members in cases of management discipline such as firings.

The war government of Vittorio Orlando also set up a high-level joint labor/management commission to draft proposals for reconstruction of Italy after the war. Participation of CGL leaders — such as Bruno Buozzi, head of the Italian Federation of Metalurgical Workers (FIOM) — on this commission amounted to collaboration with the plans and goals of the business class.

This increasing collaboration with the war government generated distrust among the rank and file. Even before the war-time austerity bore down on working people, participation in the war was not popular in the working class communities of northern Italy. Opposition to the war was especially intense in the big industrial city of Turin, center of Italy’s auto industry. In reaction to Italy’s entry into the world war in 1915, there was a two-day general strike against the war on May 17–18, which led to prolonged and bloody clashes with the police.

When the Socialist Party’s parliamentary representatives voted against the war budget in 1915, their action reflected this deep-seated anti-war feeling among their working class constituency.

But the collaboration of the labor leadership with the war government and the institutions of wartime labor discipline had the effect of sowing doubts about that leadership in the minds of many workers.

One of the first indications of the widening gap between leaders and the rank and file in the CGL unions was the opposition of rank and file activists to the national FIOM contract in March of 1919. In the months immediately after the war, the industrial firms were willing to grant concessions to labor organizations in order to avoid disruption of their efforts to quickly convert from production of arms to civilian production. This situation led to a massive strike wave as workers took advantage of this situation.

The employers were particularly willing to grant concessions on pay and hours in exchange for greater control over the labor process. This is precisely what the FIOM officials agreed to, reflecting the bureaucratization of the FIOM, whose top officials did not have to work under the conditions of the contracts. In exchange for a wage increase and the eight-hour day, restrictions were imposed on rapid strike action and the in-plant organizations of the workers were not permitted to be active during working hours. The workers also had to work a full day on Saturdays instead of half-days as before. At the next FIOM congress this contract faced blistering criticism from the Turin delegates.

The growing conflict between the rank and file and the institutional leaders of the Italian labor movement led to the emergence of new organizations, of a more grassroots character. This took two main forms: (1) The movement for shop stewards’ councils, independent of the established trade union hierarchy, built up by the rank and file activists of the CGL unions, mainly in Turin; and (2) the emergence and growth of a dissident union, the Unione Sindacale Italiana (Italian Syndicalist Union — USI).

Origins of the USI

The USI had originated from an anarchist-inspired rank and file opposition within the CGL unions. With the growth of professional trade union hierarchies and an increasing orientation of official trade unionism to electoral politics, the reaction of the anarchists was the development of dissident rank-and-file groups — called “committees for direct action,” beginning around 1908.

By the time of the Modena Congress of Direct Action Committees in 1912, there were 90,000 participants in these committees. It was decided at that congress that the movement for a more militant, non-bureaucratic workers movement had sufficient mass support to launch a new labor organization, and thus the USI was born. By 1914 the USI had grown to 150,000 members.

The USI had low dues and no hierarchical, professional trade union leadership like the CGL; it was based on horizontal links between militant associations of workers in the various workplaces. The main focus was the unity of the local unions from the different sectors in particular communities but the USI did have a major national federation in the metal sector, which grew to 30,000 members in 1920.

USI’s method of organization was mobilization of workers around direct action, and it believed that a social transformation could be achieved through “an expropriating general strike” — essentially a generalized “active strike” in which workers continue production under their own control. The USI was the Italian counterpart of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in this country.[3]

Origins of the Turin Shop Stewards’ Movement

As the war was coming to an end the experience of the British shop stewards’ movement was beginning to register in Turin, through reports in the local leftwing press. Though the British shop stewards’ movement provided the original model for the development of new shop organization in Turin, the concepts were modified by workers to meet the needs of the Italian situation. A campaign for a new form of shop organization developed through countless smallgroup discussions, in local “socialist circles”, workers’ education centers, and in workplaces.

A group of Socialist Party activists, including Palmiro Togliatti, Antonio Gramsci[4], and Umberto Terracini, set up a magazine, L’Ordine Nuovo, to popularize ideas of grassroots shop organization and to serve as a forum for workers to discuss what form such organization should take to meet the needs of their situation. Though the magazine’s founders were active in the Socialist Party, anarchists also participated; the magazine was independent, it had an open-ended, non-party character. This made the magazine well-suited to a movement dedicated to developing a heightened unity in the workforce.

To understand the new type of organization that was evolved, it is necessary to consider the problems that rank-and-file activists were trying to solve:

Lack of Rank-and-File Participation. The typical in-plant organization existing at that time in the FIOM, and other CGL unions as well, was the “internal commission” (equivalent to a shop committee in this country). In the early union contracts these were ad hoc committees set up to deal with grievances but eventually they became permanent bodies for representing the local plant workforce in dealing with management. The Turin rank-and-file activists criticized the existing internal commissions as essentially a union oligarchy, making decisions without the participation of the mass of workers.

Divisions between Union Members and Non-members. Though the unions had been entrenched in contract bargaining with employers for some time, union membership was always voluntary — at times the union membership were even a minority who had to mobilize the rest of the workforce as struggles emerged. A problem that confronted the workplace activists was that of involving the non-union workers in a developing unity of the workforce. This was an important difference from the situation confronted by the British shop stewards’ movement, where British craft unions typically had closed shop contracts.

Divisions by Craft and Ideology. The voluntary nature of union membership had also facilitated the rise of dissident unions, such as the USI[5], often reflecting ideological divisions among workers. Other divisions in the workforce in the factories in Turin were that between the blue collar workers and white collar workers, and between the machine operators, who typically belonged to the FIOM, and the skilled technicians, who had their own craft union. It was perceived that the unity of the workforce could best be achieved by a form of organization that was independent of any of the existing trade unions.

Rise of the New Shop Organizations

The first of the new shop stewards’ organizations was developed at a Fiat plant at the end of August, 1919, and quickly spread to to other plants in Turin throughout September and October. The new organizations were built initially without any authorization from the CGL unions.

The new organization was directly based in the group of people who work together in a particular workshop or department. Typically there would be a shop steward elected for each group of 15 or 20 or so people. The elections of the shop stewards took place right in the workplace, during working hours. The shop steward was expected to reflect the will of his co-workers who had elected him, and was subject to immediate recall if his co-workers so desired. The assembly of all the shop stewards in a given plant then elected the “internal commission” for that facility. But this new internal commission was now directly, constantly responsible to the body of shop stewards, which was called the “factory council.”

On October 20th, an assembly of all the shop stewards from nearly 20 plants in the auto and metal-working sector set up a “Study Committee for Factory Councils” to develop a specific program that would embody the conclusions that the movement had been working towards. The movement was now driving towards re-organization of the local union organization of FIOM in Turin and this was discussed at another assembly of shop stewards from over 30 plants, representing 50,000 workers, which took place on October 31st. This assembly adopted a program prepared by the “Study Committee,” which was the outgrowth of the countless discussions amongst the workforce [6]. The program called for re-election of shop stewards every six months, and required them to “hold frequent referenda on social and technical questions and to call frequent meetings to...” consult with the people who elected them before making decisions.

Throughout 1919 the USI had been calling for a “revolutionary united front” between the workers of the CGL, USI and the independent rail and maritime transport unions. The USI envisioned a unity that could overcome the major ideological division within the Italian working class, that is, the division between supporters of the Socialist Party and those sympathetic to the anarchists [7]. The shop stewards’ program responded positively to this initiative, clearly giving USI members equal right to be elected as shop stewards alongside members of the FIOM. The Turin movement thus interpreted the idea of a “united front” in terms of the unity of the workforce comprised in the shop councils.

Anarhija anarhisti anarhizam

Istorija Italije

Radnici

Fabrike Italija izmedju dva svetska rata komunizam fasizam socijalizam radnicki pokret marksizam ...

International shipping

Paypal only

(Države Balkana: Uplata može i preko pošte ili Western Union-a)

1 euro = 117.5 din

For international buyers please see instructions below:

To buy an item: Click on the red button KUPI ODMAH

Količina: 1 / Isporuka: Pošta / Plaćanje: Tekući račun

To confirm the purchase click on the orange button: Potvrdi kupovinu (After that we will send our paypal details)

To message us for more information: Click on the blue button POŠALJI PORUKU

To see overview of all our items: Click on Svi predmeti člana

Ako je aktivirana opcija besplatna dostava, ona se odnosi samo na slanje kao preporučena tiskovina ili cc paket na teritoriji Srbije.

Poštarina za knjige je u proseku 133-200 dinara, u slučaju da izaberete opciju plaćanje pre slanja i slanje preko pošte. Postexpress i kurirske službe su skuplje ali imaju opciju plaćanja pouzećem. Ako nije stavljena opcija da je moguće slanje i nekom drugom kurirskom službom pored postexpressa, slobodno kupite knjigu pa nam u poruci napišite koja kurirska služba vam odgovara.

Ukoliko još uvek nemate bar 10 pozitivnih ocena, zbog nekoliko neprijatnih iskustava, molili bi vas da nam uplatite cenu kupljenog predmeta unapred.

Novi Sad lično preuzimanje (pored Kulturne stanice Eđšeg) ili svaki dan ili jednom nedeljno zavisno od lokacije prodatog predmeta (jedan deo predmeta je u Novom Sadu, drugi u kući van grada).

Našu kompletnu ponudu možete videti preko linka

https://www.kupindo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakPredmeta

Ukoliko tražite još neki naslov koji ne možete da nađete pošaljite nam poruku možda ga imamo u magacinu.

Pogledajte i našu ponudu na limundu https://www.limundo.com/Clan/H.C.E/SpisakAukcija

Slobodno pitajte šta vas zanima preko poruka. Preuzimanje moguce u Novom Sadu i Sremskoj Mitrovici uz prethodni dogovor. (Većina knjiga je u Sremskoj Mitrovici, manji broj u Novom Sadu, tako da se najavite nekoliko dana ranije u slucaju ličnog preuzimanja, da bi knjige bile donete, a ako Vam hitno treba neka knjiga za danas ili sutra, obavezno proverite prvo preko poruke da li je u magacinu da ne bi doslo do neprijatnosti). U krajnjem slučaju mogu biti poslate i poštom u Novi Sad i stižu za jedan dan.

U Novom Sadu lično preuzimanje na Grbavici na našoj adresi ili u okolini po dogovoru. Dostava na kućnu adresu u Novom Sadu putem kurira 350 dinara.

Slanje nakon uplate na račun u Erste banci (ukoliko ne želite da plaćate po preuzimanju). Poštarina za jednu knjigu, zavisno od njene težine (do 2 kg), može biti od 170-264 din. Slanje vise knjiga u paketu težem od 2 kg 340-450 din. Za cene postexpressa ili drugih službi se možete informisati na njihovim sajtovima.

http://www.postexpress.rs/struktura/lat/cenovnik/cenovnik-unutrasnji-saobracaj.asp

INOSTRANSTVO: Šaljem po dogovoru, ili po vašim prijateljima/rodbini ili poštom. U Beč idem jednom godišnje pa ako se podudare termini knjige mogu doneti lično. Skuplje pakete mogu poslati i po nekom autobusu, molim vas ne tražite mi da šaljem autobusima knjige manje vrednosti jer mi odlazak na autobusku stanicu i čekanje prevoza pravi veći problem nego što bi koštala poštarina za slanje kao mali paket preko pošte.

Ukoliko kupujete više od jedne knjige javite se porukom možda Vam mogu dati određeni popust na neke naslove.

Sve knjige su detaljno uslikane, ako Vas još nešto interesuje slobodno pitajte porukom. Reklamacije primamo samo ukoliko nam prvo pošaljete knjigu nazad da vidim u čemu je problem pa nakon toga vraćamo novac. Jednom smo prevareni od strane člana koji nam je vratio potpuno drugu knjigu od one koju smo mu mi poslali, tako da više ne vraćamo novac pre nego što vidimo da li se radi o našoj knjizi.

Ukoliko Vam neka pošiljka ne stigne za dva ili tri dana, odmah nas kontaktirajte za broj pošiljke kako bi videli u čemu je problem. Ne čekajte da prođe više vremena, pogotovo ako ste iz inostranstva, jer nakon određenog vremena pošiljke se vraćaju pošiljaocu, tako da bi morali da platimo troškove povratka i ponovnog slanja. Potvrde o slanju čuvamo do 10 dana. U 99% slučajeva sve prolazi glatko, ali nikad se ne zna.

Ukoliko uvažimo vašu reklamaciju ne snosimo troškove poštarine, osim kada je očigledno naša greška u pitanju.

Predmet: 69356149