Walt Withman - LEAVES OF GRASS (najkompletnije izdanje

| Cena: |

| Želi ovaj predmet: | 12 |

| Stanje: | Polovan bez oštećenja |

| Garancija: | Ne |

| Isporuka: | Pošta Lično preuzimanje |

| Plaćanje: | Tekući račun (pre slanja) Lično |

| Grad: |

Novi Sad, Novi Sad |

Godina izdanja: 2004

ISBN: 978-1-59308-083-2

Jezik: Srpski

Autor: Strani

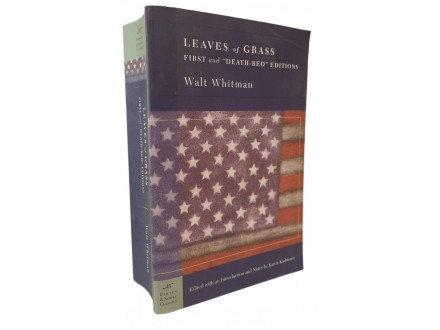

Leaves of Grass (Barnes & Noble Classics Series): First and `Death-Bed` Editions Paperback – December 25, 2004, by Walt Whitman (Author), Karen Karbiener (Editor, Introduction)

Product details

Publisher: Sterling Publishing; Trade Paperback Edition (December 25, 2004)

Language: English

Paperback: 960 pages

Item Weight: 1.73 pounds

Dimensions: 5.25 x 1.92 x 8 inches

Posveta priređivačice izdanja na najavnoj strani.

Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman, is part of the Barnes & Noble Classics series, which offers quality editions at affordable prices to the student and the general reader, including new scholarship, thoughtful design, and pages of carefully crafted extras. Here are some of the remarkable features of Barnes & Noble Classics:

New introductions commissioned from today`s top writers and scholars

Biographies of the authors

Chronologies of contemporary historical, biographical, and cultural events

Footnotes and endnotes

Selective discussions of imitations, parodies, poems, books, plays, paintings, operas, statuary, and films inspired by the work

Comments by other famous authors

Study questions to challenge the reader`s viewpoints and expectations

Bibliographies for further reading

Indices & Glossaries, when appropriate

All editions are beautifully designed and are printed to superior specifications; some include illustrations of historical interest. Barnes & Noble Classics pulls together a constellation of influences—biographical, historical, and literary—to enrich each reader`s understanding of these enduring works.

When Leaves of Grass was first published in 1855 as a slim tract of twelve untitled poems, Walt Whitman was still an unknown. But his self-published volume soon became a landmark of poetry, introducing the world to a new and uniquely American form. The `father of free verse,` Whitman drew upon the cadence of simple, even idiomatic speech to `sing` such themes as democracy, sexuality, and frank autobiography.

Throughout his prolific writing career, Whitman continually revised his work and expanded Leaves of Grass, which went through nine, substantively different editions, culminating in the final, authoritative `Death-bed Edition.` Now the original 1855 version and the `Death-bed Edition` of 1892 have been brought together in a single volume, allowing the reader to experience the total scope of Whitman`s genius, which produced love lyrics, visionary musings, glimpses of nightmare and ecstasy, celebrations of the human body and spirit, and poems of loneliness, loss, and mourning.

Alive with the mythical strength and vitality that epitomized the American experience in the nineteenth century, Leaves of Grass continues to inspire, uplift, and unite those who read it.

From Karen Karbiener’s Introduction to Leaves of Grass: First and `Death-Bed` Editions

`Whitman, the one pioneer. And only Whitman,` wrote D. H. Lawrence in 1923. `No English pioneers, no French. No European pioneer-poets. In Europe the would-be pioneers are mere innovators. The same in America. Ahead of Whitman, nothing` (Woodress, ed., Critical Essays on Walt Whitman, p. 211). The sentiments were echoed by the likes of F. O. Matthiessen, William Carlos Williams, and Allen Ginsberg. Langston Hughes named Whitman the `greatest of American poets`; Henry Miller described him as `the bard of the future` (quoted in Perlman et al., eds., Walt Whitman: The Measure of His Song, pp. 185, 205). Even his more cynical readers recognized Whitman’s position of near-mythical status and supreme influence in American letters. `His crudity is an exceeding great stench but it is America,` Ezra Pound admitted in a 1909 article; he continued: `To be frank, Whitman is to my fatherland what Dante is to Italy` (Perlman, pp. 112–113). `We continue to live in a Whitmanesque age,` said Pablo Neruda in a speech to PEN in 1972. `Walt Whitman was the protagonist of a truly geographical personality: The first man in history to speak with a truly continental American voice, to bear a truly American name` (Perlman, p. 232). Alicia Ostriker, in a 1992 essay, claimed that `if women poets in America have written more boldly and experimentally in the last thirty years than our British equivalents, we have Whitman to thank` (Perlman, p. 463).

How did a former typesetter and penny-daily editor come to write the poems that would define and shape American literature and culture?

Whitman’s metamorphosis in the decade before the first publication of Leaves of Grass in 1855 remains an intriguing mystery. Biographers concede that details about Whitman’s life and literary activities from the late 1840s to the early 1850s are extremely hard to come by. `Little is known of Whitman’s activities in these years,` writes Joann Krieg in the 1851–1854 section of her Whitman Chronology (most other years have month-to-month commentaries). Whitman was fired from his job at the New Orleans Daily Cresent in the summer of 1848, then resigned from his editorship of the Brooklyn Freeman in 1849. Though he continued to write for several newspapers during the next five years, his work as a freelancer was irregular and his whereabouts difficult to follow. He seems also to have tried his hand at several other jobs, including house building and selling stationery. One wonders if Walt’s break from the daily work routine had something to do with his poetic awakening. Keeping to a regulated schedule in the newspaper offices had been a struggle for him, and he had been fired several times for laziness or `sloth.` Charting his own days and ways—in particular, working as a self-employed carpenter, as had his idiosyncratic father—may well have enabled him to think `outside the box` and toward the organic, freeform qualities of Leaves.

Purposefully dropping out of workaday life and common sight suggests that Whitman may have intended to obscure the details of his pre-Leaves years, and there is further evidence to support the idea that Whitman consciously created a `myth of origins.` In his biography of Whitman, Justin Kaplan quotes the poet on the mysterious `perturbations` of Leaves of Grass: It had been written under `great pressure, pressure from within,` and he had `felt that he must do it` (p. 185). To obscure the roots of Leaves and build the case for his original thinking, Whitman destroyed significant amounts of manuscripts and letters upon at least two occasions; as Grier notes in his introduction to Notebooks and Unpublished Prose Manuscripts, `one is continually struck by [the] omissions and reticences` of the remaining material (vol. 1, p. 8). Indeed, some of the notes surviving his `clean-ups` were reminders to himself to `not name any names`—and thus to remain silent concerning any possible readings or influences. `Make no quotations, and no reference to any other writers.—Lumber the writing with nothing,` Whitman wrote to himself in the late 1840s. It was a command he would repeat to himself several times in the years preceding the publication of Leaves.

Whitman’s friends and critics also did their share to create a legend of the writer and his explosive first book. In the first biographical study of Whitman, John Burroughs claimed that certain individuals throughout history `mark and make new eras, plant the standard again ahead, and in one man personify vast races or sweeping revolutions. I consider Walt Whitman such an individual` (Burroughs, `Preface` to Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person). Others insisted that Leaves of Grass was the product of the `cosmic consciousness` Whitman had acquired around 1850 (Bucke, Walt Whitman, p. 178) or a spiritual `illumination` of the highest order (Binns, A Life of Walt Whitman, p. 69–70).

What sort of experience could inspire such a personal revelation? For a man just awakening to the inhumanity of slavery and the hidden agendas of the Free Soil stance, witnessing a slave auction might do it. This was but one of the life-altering events that occurred during Whitman’s three-month sojourn in New Orleans in 1848. Another, substantiated by his poetry rather than Whitman’s own word, was an alleged homosexual affair. Several poems in the sexually charged `Calamus` and `Children of Adam` clusters of 1860 are suggestive of an intense and liberating romance in New Orleans. The manuscript for `Once I Passed Through a Populous City` has the lines `man who wandered with me, there, for love of me, / Day by day, and night by night, we were together.` `Man` was changed to `woman` in the final draft of the poem; see Whitman’s Manuscripts: Leaves of Grass (1860), edited by Fredson Bowers, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955, p. 64. In `I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing,` the poet describes breaking off a twig of a particularly stately and solitary tree: `Yet it remains to me a curious token, it makes me think of manly love.` The emotional release of `coming out` might well explain the spectacular openness and provocative energy of Leaves of Grass; additionally, Whitman’s identification of his `outsider status` could have helped spark his empathy for women, Native Americans, and other marginalized groups that are celebrated in the 1855 poems.

About the Author

Karen Karbiener received a Ph.D. from Columbia University and currently teaches at New York University. She also wrote the introduction and notes for the Barnes & Noble Classics edition of Frankenstein.

Volt Vitman (engl. Walt Whitman; Vest Hils, 31. maj 1819 – Nju Džerzi, 26. mart 1892) bio je američki pesnik.

U mladosti je živeo nemirnim životom menjajući mnoge poslove. Sam štampa svoje glavno delo, poznatu knjigu pesama Vlati trave, koja se posle pojavila u mnogim izdanjima, na mnogim jezicima. Piše joj predgovor, u kojem iznosi zahteve za novom američkom književnošću. Vlati trave je zbirka pesama u slobodnom stihu, koja na snažan način slavi individualizam Amerike, demokratiju i bratstvo među ljudima, te živo i ushićeno opisuje američki život, posebno Njujork. Delo je proglašeno nemoralnim zbog slobodne obrade polnog života (posebno homoerotskih tonova), pa pesnik biva neshvaćen od savremenika. Međutim, moderna kritika ga smatra jednim od najvažnijih stvaralaca u istoriji američke književnosti.

Iako se rasprava o Vitmanovoj seksualnosti i dalje vodi, uobičajeno se smatra homoseksualcem ili biseksualcem. Pretpostavke i zaključci o njegovoj seksualnosti izvedeni su iz njegove poezije, premda se isti osporavaju. Njegova poezija predstavlja ljubav i seksualnost na ovozemaljski način, lišen moralne prepredenosti religije, tipičan za Američku kulturu tog vremena, koja smatra individualnost kao jednu od najvrednijih vrlina. Takođe, njegova dela su nastala u prvom razdoblju 19. veka, pre medicinske klasifikacije seksualnosti.

Vitman je tokom svog života imao veliki broj intenzivnih prijateljstava sa muškarcima i mladićima. Određeni biografi su naveli kako smatraju da bez obzira na intenzitet tih odnosa i prisnost, oni zapravo nikada nisu bili karnalni.

Smatra se da je Piter Dojl bio Vitmanova velika ljubav. Dojl je radio kao kondukter kada su se on i Volt upoznali oko 1866. godine. Sledećih par godina su bili nerazdvojni.

Oskar Vajld je upoznao Vitmana tokom svog boravka u Americi 1882. godine, te je kasnije izjavio Džordžu Sesilu Ivsu, jednom od prvih aktivista za prava homoseksualaca, da je Vitmanova seksualna orijentacija izvan sumnje: „Imam poljubac Volta Vitmana još uvek na mojim usnama.

Leaves of Grass poetska je zbirka američkog pesnika Valta Vhitmana (1819–1892). Iako je prvo izdanje objavljeno 1855. godine, Vhitman je veći deo svog profesionalnog života proveo pišući i preispitujući Leaves of Grass, revidirajući ga više puta do smrti. To je rezultiralo veoma različitim izdanjima tokom četiri decenije – prvom, malom knjigom od dvanaest pesama i poslednjom, zbirkom od preko 400.

Pesme „Vlati trave“ su labavo povezane, a svaka predstavlja Whitmanovu proslavu njegove filozofije života i čovečanstva. Ova knjiga je karakteristična po tome što je razgovarala o uživanju u čulnim zadovoljstvima u vreme kada su se ovakvi otvoreni prikazi smatrali nemoralnim. Tamo gde se mnogo prethodnih poezija, posebno engleskog, oslanjalo na simboliku, alegoriju i meditaciju o religioznom i duhovnom, listovi trave (posebno prvo izdanje) uzdizali su telo i materijalni svet. Vhitmanova poezija pod utjecajem Ralpha Valda Emersona i transcendentalističkog pokreta, samog roda romantizma, hvali prirodu i ulogu pojedinca u njoj. Međutim, slično Emersonu, Whitman ne umanjuje ulogu uma ili duha; radije uzdiže ljudski oblik i ljudski um smatrajući ih vrednima poetičke pohvale.

Uz jedan izuzetak, pesme se ne rimuju i ne slede standardna pravila za metar i dužinu linija. Među pesmama u zbirci su „Pesma o sebi“, „Ja pevam telo električno“ i „Iz kolijevke se beskrajno ljuljaju“. Kasnija izdanja uključivala su Whitmanovu elegiju ubijenog predsjednika Abrahama Lincolna, „Kad su jorgovan trajali u Dooriard Bloom’d“.

Leaves of Grass bio je veoma kontroverzan u svoje vreme zbog svojih eksplicitnih seksualnih predodžbi, a Vhitmana su podvrgavali ruganju mnogih savremenih kritičara. Međutim, tokom vremena, zbirka je prodrla u popularnu kulturu i postala je prepoznata kao jedno od centralnih dela američke poezije.

Kad su čuvenog engleskog logičara i filozofa Alfreda Norta Vajtheda (Alfred North Whitehead) upitali da li postoji nešto originalno i specifično američko on je odgovorio samo jednom rečju: „Vitmen”. No to se dogodilo trideset godina nakon pjesnikove smrti, a i originalnost nije osobina koja je ikada bila poricana u ovom slučaju. Ono što je poeziji Volta Vitmena (Walt Whitman, 1819–1892) nedostajalo, po mišljenju nekih od kritičara njegove zbirke Vlati trave (Leaves of Grass, 1855), bile su primjese umjetnosti. Tako, na primjer, jedan londonski časopis te iste godine tvrdi da je “Volt Vitmen isto toliko upoznat s umjetnošću koliko svinja s matematikom.” Šta je, dakle, sadržavala prva Vitmenova zbirka od dvanaest pjesama, koja na koricama nije čak imala ni ime autora već samo njegovu sliku, da izazove ovakvu ocjenu? Šta je omogućilo da se nešto što je smatrano bizarnim, barbarskim i neukim pretvori, po gotovo opštem mišljenju, u jedan od najviših uzleta američke poezije?

Iako je zbirka Vlati trave doživjela od Vitmenove smrti osam izdanja kroz koje je rasla, proširivala se i mijenjala, osnovne osobine poezije, što se tiče forme kao i sadržaja, ostajale su iste i podjednako neobične, posebno za devetnaesto stoljeće. Vitmen, naime, uvodi u poeziju slobodni stih koji ne sadrži ni rimu, ni fiksiran metar ni druga uobičajena versifikacijska sredstva. Ona su zamijenjena kolokvijalnim tonom i stihovima nepravilne dužine, otvorenom formom koja pjesnički ritam dobija iz nešematizovane smjene naglašenih i nenaglašenih slogova, Vitmenov slobodni stih, iako ne originalan, jer se pojavljuje na engleskom jeziku već početkom 17. stoljeća u prevodu Biblije, jeste krajnje ostvarenje romantičarske zamisli organske forme, oblika koji treba da potiče iz samog djela i da izražava njegovu posebnost.

Sadržaj ili poruke Vitmenovih najkarakterističnijih pjesama takođe su u svojoj suštini romantičarske ili, govoreći u američkim okvirima, trascendentalističke, no ideje romantizma ili transcendentalizma u njegovoj poeziji su dovedene do svojih krajnjih mogućnosti. Junak tipičnog romantičaskog spjeva kao što je, recimo, Bajronov (Byron) Čajld Harold (Childe Harold) ili Šelijev (Shelley) Oslobođeni Prometej (Prometheus Unbound) jeste čovjek koji, iako podsjeća na autora, ipak nosi masku neke druge istorijske ili izmišljene ličnosti i prema tome i ne progovara glasom pjesnika. Vitmen, međutim, nema obzira prema pjesničkim konvencijama, pa zato i može da prvu strofu svoje najčuvenije „Pjesme o samom sebi” (“Song of Myself”) započne ovako...

KC

Predmet: 73036945